solo projects

Correspondence

Correspondence fuses together electromechanical components, kinetics, video, optical illusions and telematic infrastructures. Referencing the chess playing pseudo automaton known as the Mechanical Turk, the work is a rather complicated way of producing a simple action of two kings on a chessboard playing a never ending loop of an endgame. The physical game powers an online game, registering as two human players on a public chess forum, forever playing the same moves.

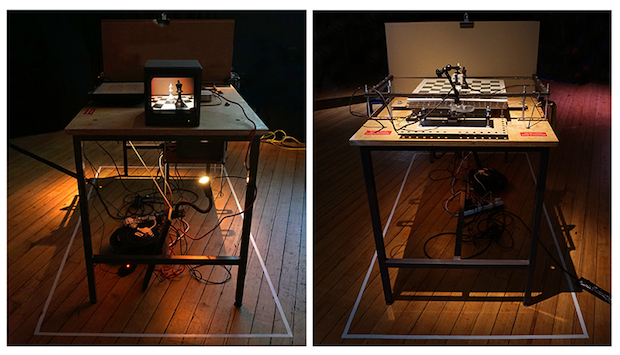

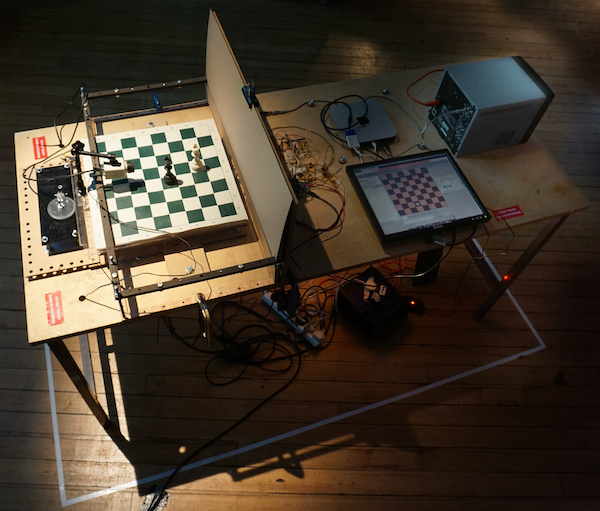

Correspondence, 2019: installation view Motorised chess board, cctv camera, video monitor,customized circuits and software, electromagnets, python script linked to public chess forum

Correspondence, 2019: installation view Motorised chess board, cctv camera, video monitor,customized circuits and software, electromagnets, python script linked to public chess forum

At one end of a workshop bench, a cctv monitor displays close-ups of two kings on a chess board. On screen, one of the kings occassionally moves across to another square with no visible means of locomotion. The movement of the piece is juddery and shaky. This is by no means the product of high quality computer generated imagery (CGI).

Behind a wooden screen that divides the table is a contraption consisting of a transparent frame straddling a chessboard. The two kings sit on the frame. A cctv camera is attached to the contraption. A motor moves the board/camera into one of three positions. Each time the board moves, it drags one of the kings with it, leaving the other behind. Whilst the screen divider stops the viewer from seeing both the cctv monitor and the contraption at the same time, walking between the two reveals a correspondence of positions.

On top of the table between these two elements, is a tangle of stripboard circuitry, an Arduino micro controller, a computer and a monitor, flat against the table. This screen shows a Firefox web browser open on the website ‘lichess.org'. An icon plan view of a chess game is visible, as well as surrounding information about who is playing, whose turn it is, and the notation of moves played. The game shown is also two kings playing in a stalemate. Each time a piece moves on the physical board and cctv monitor, the virtual game also updates after a short lag to reflect this.

Beneath the table hangs another monitor. Upside down close-ups of a man’s face engaged in thinking, staring or holding his head in his hands are cut together in a way that he is facing himself. The position creates a spatial relationship between what the man is looking at and the things on top of the table.

Workflow:

Attached to the underside of the motorised microprocessor controlled chess board are four electromagnets, which, when instructed by a microprocessor, in turn hold or release two chess pieces (containing magnets). The camera attached to the board is live, fed to the monitor at the opposite end of the table. This set up creates an inverse relationship between which piece is moved by the machine, and what is perceived to be happening on screen. The backdrop screen also acts to obscure the position of the camera relative to the room the piece is exhibited in.

As the micro-controller sends signals to the motor and electromagnets, it also sends data to a Python script on the desktop computer that correspond to the on/off state of the electromagnets. Python uses two webdrivers to log into the Lichess website as two different human players; it plays a game stored in an array to the stalemate position and then listens for instructions from the Arduino. This maps the physical moves of the installation to those in the virtual world. The Lichess game is visible to anyone browsing the site to watch a human versus human game. The Lichess site database also logs each game played so that they can be saved or downloaded. The video playing beneath the table is of close-ups of Garry Kasparov, ex world chess champion, either playing chess against humans, or in the moment he is defeated by a computer.

Background:

This project began with an inquiry into the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI), primarily through the lens of the history and present use of AI used in the game of chess. In the Encyclopaedia Britannica’s 1980 Yearbook of Science and The Future (Calhoun, 1979, p.298), an article on Computer Chess gives the following prediction:

“New advances in artificial intelligence implemented on computers very different from those now in use will probably be needed in order to produce a chess-playing program of world championship calibre. Even though tremendous progress has already been made, the human world chess champion seems safe from defeat by a machine, at least in the 20th century. It would be foolish to predict any limitations on what computers might be able to do beyond the year 2000.”

The then reigning World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov was defeated by IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer under tournament conditions in 1997.

By 2018, away from the confines of chess machines, headlines and policy papers discuss recent advances in AI and Machine Learning (ML), as having a ‘potentially transformational’ impact (BEIS, 2018) in many areas of work and life. US venture capital funding for AI start-ups grew 72% to $9.3B in 2018 (Greenman, 2019).

In its State of AI Divergence Report 2019, MMC ventures, a venture capitalist firm charts out the adoption of AI as societally disruptive and profitable for the ‘adopters’ rather than the ‘laggards’(Kelnar, 2019). As with any rush into a new, exciting and profitable area, over-claiming the use of AI is also prevalent. Another MMC report, latched onto by broadsheets, based on publicly available data including interviews with company executives and estimates that of 2, 830 AI start-ups in Europe in 2018, 40% do not actually use artificial intelligence in any of their products (Ram, 2019).

Companies that overstate their use of AI whilst relying on a hidden workforce of humans essentially pretending to be computers, is a form of what Kirby (2010) termed ‘diegetic prototyping’. The diegesis - the fictional world created within a film - contains working examples of future technologies packaged within its fiction as if they exist as a matter of course. Whilst they may not exist in the real world, their use can attract funding, create a discourse that can generate need or acceptance, in short, imagine a future in order to make it happen. Pseudo-AI start-ups can be viewed as using these same strategies within the colossal fictions of the global capitalist marketplace. With this in mind, what can other technological narratives based on ideas of overstated artificial intelligence from the past inform us about the present? I will begin by looking at a chess-playing pseudo-automaton - the Mechanical Turk.

The Mechanical Turk

The ‘Turk’ was unveiled by Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1770 Vienna. Kempelen claimed that he had built a mechanical man that could beat humans at the game of chess (Schwartz, 2016). What was claimed as an automaton marvel consisted of a life-sized mechanical man in a turban seated behind a large cabinet ready to play the chess set on top of it. Opening the cabinet doors revealed myriad levers, cogs and clockwork machinery. Once brought to life through a winding key, the ‘Turk’ would begin to play.

The responses to the ‘Turk’ were varied, running the full gamut from awestruck wonder, horror at a marvel that had surpassed human intelligence or, as in the case of the writer Poe, suspicion that at the bottom of it all lay not an automaton, but a human, hidden inside the cabinet. Whilst many attempted to guess how the ‘Turk’ actually worked, much misinformation was printed during the 85 years that the ‘Turk’ was touring (Standage, 2003, p.194).

The account of Silas Weir Mitchell, the son of the ‘Turk’s’ last owner, revealed that many elements of the mechanism were designed to throw people off the trail from the fact that the cabinet was able to easily conceal a full-sized adult, who operated the machine and responded to the moves of the human player outside (Standage pg 208).

As the story of the ‘Turk’ is told and retold, the anonymous person(s) inside the box tasked with operating the levers remains invisible. For Schwartz, the emphasis on the ‘Turk’ rather than the human ghost in the machine is a sign that we are more than willing to ignore the human operator (and by extension the conditions in which they work) for the “romance of a thinking machine.” (Shwartz, 2016, p.7) Whilst von Kempelen’s ‘Turk’ gripped the imagination of audiences over its 85 year history in the belief that a mechanical chess player was or might be possible, the reality was that there also existed an invisible procession of chess players “willing to merge their identity with the machine for a bit of extra cash” (Shwartz, 2015, p.46).

Seen through the lens of design fictions, the Mechanical Turk shortcuts a solution to a problem in the same way as a non-AI-AI-startup. If the concept needs expensive or unfeasible R&D work in order to provide a proof of concept - an autonomous man - then by cloaking the true ‘mechanism’ and opting for pseudo- autonomy the start-up can still draw in and test the reaction of an audience. The autonomy of the actual chess player(s), hidden inside the box in cramped conditions, paid to work and sworn to secrecy, is of another order entirely, and is reminiscent of Amazon’s hidden workers within its M-Turk interface.

M-Turk

Amazon Turk (M-Turk) is a website service that offers an exchange between people requesting tasks to be done that a computer finds difficult, with an invisible workforce - Turkers - who are willing to do it for a small fee. Schwartz (2016) equates the invisibility of the person/s inside the ‘Turk’ with the invisibility of the precarious workers ‘behind’ the interface of Amazon’s website.

The interface anonymises the labour exchange as impersonal and computer-like. Although a ‘requester’ knows that they are essentially communicating via the interface with a human, the entire feel is one of utilising a program and hitting enter. For Schwartz (2016), the effect of this mediation creates (and he argues is designed to create) an interaction that appears not to be between a human and a human, but a human and software. For researchers in a number of fields seeking diverse survey samples, however, the M-Turk marketplace is exactly what they are using in order to study human beings (Samuel, 2018).

The pseudo-automation of the ‘Mechanical Turk’ which inspired the M-Turk business model has in turn become a place in which not only academic survey research takes place, but where artists critique and/or exploit its function. Work such as Watchtower by James Coupe (2017), examines how surveillance has become domesticated, and pays M-Turk workers to record videos of their mundane routines, upload them and organises them into a series.

The history and mythology of the original ‘Mechanical Turk’ continues to influence artists who explore its effect and meaning. In the film The Mechanical Turk (2006) by Gavin Turk (no relation), the artist impersonates Kemplen’s automaton. The human artist Gavin Turk performs as the pseudo-automaton ‘Turk’ repeatedly performing an endless knight’s tour of the chess board, whereby the knight moves to occupy every space on the board once. Whilst the film reworks the position of the human of the original, as the moves and the film form a loop, what starts out as mimicry, ends up as a temporal pseudo-automaton. As Duchamp would have it, while not all artists are chess players, all chess players are artists (cited in Schwarz, 1970 p.49).

Scot Kildall follows in the footsteps of other artists such as Duchamp who make art from chess and chess from art. Playing Duchamp is an artwork by Scott Kildall that modifies GNU chess code in order to mimic Marcel Duchamp’s chess style. For Kildall, designing a computer algorithm to play like a specific person presented what he calls, in a somewhat understated fashion, a “challenging problem” (Kildall, 2010). He used archive of 72 recorded tournament games played by Duchamp, together with conversations with Jennifer Shahade, a chess and Duchamp expert. From this he “abstracted various principles regarding his chess strategies”, including mistakes made during mid-game through apparent loss of concentration, a favoured hypermodern style of playing etc.

The discourse around the work frames the project as playing with Duchamp’s ghost, a near approximation as if playing with the dead artist. As an artistic gesture, or an attempt to combine programming skills with the new media projects that Kildall would later move into, this is an interesting narrative claim. At base, this rekindles a love affair with the idea that we can abstract and reduce down to a ‘truth’ in a given circumstance through computational sophistication, or what Bridle (2018, p.4) calls ‘computational thinking’ , that is, that any given problem can be solved by the application of computation.

Whilst Kildall relied on the database memory of Duchamp’s moves, and consulted an expert and Duchamp historian, the claim made for the artwork is in danger of overstating its case and falling into the same solutionism that the ‘Mechanical Turk’ signalled during a previous era. Against the backdrop of the Enlightenment’s obsession with determinism and free will, a philosopher’s standing went hand in hand with their ability to explain both nature and society in relation to mechanical principles (Schaffer, 1999, p.128). Kildall’s algorithm simulates mistakes but does not get bored. It might be programmed to avoid repetition in games, but not because it abhors it.

Disappearing Act - Magic and Illusion in Art

Whilst the Mechanical Turk could be seen as an actual automaton, it could also be taken as a form of magic trick which implies a different “unique and distinctively intellectual aesthetic experience” (Leddington, 2016, p.2 ). Citing the performer Teller of Penn & Teller, the audience in a magic show experiences magic “as real and unreal at the same time”; something that for Stromberg (2012) “goes straight to the brain; its essence is intellectual.” The simultaneous conflicting positions that this creates quite literally makes the head hurt. Leddington (2016) argues that magic performs a twist on the traditional aesthetic paradox, creating illusions of impossibility that together with an audience’s active disbelief unseat magic from traditional aesthetic categories. Fascinated by the ‘Turk’, but not believing it as an automaton, Poe was in the position of an audience member in a magic show, attempting to eliminate different possibilities in how the trick was turned. In wanting to create some form of chess automaton in my piece Correspondence, I sought to investigate a way in which a trick could both be revealed and staged simultaneously.

Correspondence developed from a consideration of the effects of AI broadly, but I was also interested on the effects of AI on correspondence chess. Historically, correspondence chess played by humans at a distance, in contrast to the ‘traditional’ over-the-board (OTB) chess games where players physically meet. It has been played using various forms of long-distance correspondence - by post, phone, radio, homing pigeon, and more recently by fax, email and through public internet chess forums and web servers. Enabled by the introduction of new technologies, many chess enthusiasts regularly play correspondence chess against humans, against AI, or in various combinations of these. As in many other areas of work and life – for example commercial business oriented chatbots – who we correspond with nowadays overlaps with what we correspond with.

Recently, elements of correspondence chess have been linked with OTB chess. In this ‘hybrid’ form, a board is connected via web infrastructure that uses radio frequency identification (RFID) chips to locate each chess piece; simultaneously, technology underneath the board moves the pieces. Projects such as ‘Square Off’ (Kickstarter, 2019) frame the appeal of their offer as being one that opens up a new world of chess playing - at a distance but in front of a real, moving board.

They claim that “The automated board is designed to reflect the move of your opponent with precision.” Watching their promotional video on the Kickstarter site, I was surprised to find that their definition of ‘reflect[ing] the move of your opponent with precision’ is of its arrival rather than the manner of its journey. Just what aspect of the ‘move’ is actually being reflected here? Artist and chess Master Marcel Duchamp claimed that the movements made in chess were akin to painting in that both shared the quality of “a drawing, a mechanical reality”(Cabanne, 1979). He felt the difference lay in the fact that, although there was beauty in the movement contained within a game of chess, this beauty did not reside in the visual domain, but in “the imagining of the movement or of the gesture... It's completely in one's gray matter.” (Cabanne, 1979, p.12).

Square Off, and other similar projects appeared to substitute the beauty of imagined movement for a special effect. Some press reports laud this new area of physical at-a-distance chess as feeling “haunted” and having a ‘Harry Potter’ quality (Holland and Cheng, 2019). This particular advertorial continues with the insight that it “can help connect family members” and “allow players with physical disabilities who can't move the pieces but can swipe a smartphone touchscreen to participate in a full-fledged, physical game of chess.”

Watching the press promo video on Kickstarter and reading the PR framing of this and competing models, made me think about both the claims and the mechanism of OBR chess, earlier correspondence chess, and a way to critique the techno-utopian realisation of artificial intelligence against a history of the automaton.

The first phase of my project involved an attempt to reduce some of the claims made by Square Off by making a basic and pointless stalemate endgame that operated in a similar fashion. Having two kings moving around on a board in this way, also resonated for me with the framing of chess as a spectacle from a previous era. Matches between grandmasters from opposing superpowers were lent the aura of a proxy war against the backdrop of the brinkmanship strategies of mutually assured destruction (MAD). I began to consider an installation framed during this era with historical trappings of the matches of the time, overlapped with the present. However, rather than beginning to narratively frame potential trajectories for the piece, I wanted to think through the materials, and the contemporary era, to hand. In reducing the experience to that of a spectator watching a pointless endgame ad infinitum, something that was framed as a ‘useful machine’ becomes a ‘pointless machine’, a cul-de-sac of novelty.

However, after experimenting with magnets attached to each of two kings, and magnetic paddles held under a chessboard board, the rudimentary effect had the same ‘Harry Potter’ quality of the somewhat more sophisticated (and admittedly appealing) Square Off board. I could imagine that two friends, having unwrapped their Square Off board (filmed and put up on youtube as one of the myriad ‘unboxing’ videos) would soon be playing this very same endgame through their $400 boards and phone app, just because.

In an ordinary game of chess everything is on the table and out in the open. The players and the audience can at a glance, see where the game is ‘at’, where everything ‘is’. For some artists using chess within their work, this is precisely the point at which their work reconfigures chess and departs. Yoko Ono’s Play it by Trust’ paints a chess board and all its pieces white. To understand the game, one can no longer glance at the board ‘as is’. Instead, the observer has to know the history of the game that unfolded to its present position. In this way, “attention is shifted from the pieces to the action itself”( Yngvason, 2009, p.9). In Ono’s piece, time becomes an important element in understanding the game-artwork and the connections that are formed to be able to follow the game at hand. I wanted to develop the piece I had experimented with in phase 1, to not only move on from the ‘Harry Potter’ like spectacle of pieces moving, but to take a strategy such as the one used by Ono with Play it By Trust that confuse where the game is ‘at’. Rather than flattening ‘the sides’ as a strategy which creates a need for a reference to a history of the positions from a starting point in order to work out a game, I wanted to concentrate on what we mean in the ‘where’ of Ono’s approach as to where everything ‘is’. I also wanted to explore strategies akin to John Cage’s Chess Pieces (1944) that allowed the artwork to function as a hybrid. Cage’s work, a painting-chessboard-musical score, ‘worked’ as a painting to be looked at, played as a chessboard or played as music. I sought out ways to devise something that was both observable chess and not-chess.

I began to consider the element of ‘correspondence’ in chess in terms of the relationship between the position of a piece and the position of the board. If both the board and one of the pieces were able to move, essentially disturbing the relationship between figure (one king) and ground (board), could a familiar game still be watched and made sense of, and even so, what would this do to an audience viscerally?

I experimented with both mental exercises, aided by drawing, and used an iterative process of prototyping that led to propping a piece of glass above the board using books as chocks, allowing the pieces to hover over the squares. I placed the board on top of pencils that would act as rollers. Bringing in my magnetic paddles, I began to move both the board and a king, producing an inverse relationship to which piece appears to move relative to the board, and which piece actually moved within the studio room I was working in. To get the white king to ‘move’ from d4 to d2, and for the black king to appear to stay in place on b2 required using a magnetic paddle on the black king that moved it the same distance as the board. For the black king, a move ‘with’ the board created a ‘not move’. For the white king, ‘not moving’ with the board, gave the appearance of a move in relation to the board.

Despite the fact that I understood the logic of what I was attempting, I continually moved the wrong piece for the effect I was after. During this phase, as I was moving things manually, I could not sit back and observe in a detached manner what the effect of what I was doing might have on a non-interacting audience. To begin to achieve some distance before beginning to design and build anything that could be powered by motors, I set up a cctv camera and monitor in order to watch it at least at one removed, framed by a monitor. This became an interesting way of reframing what was going on physically through another medium, allowing a different point of view. As I began testing using this set up, I realised that I could incorporate an in-camera effect used in the film industry. In a rudimentary (gaffer tape) fashion I tied the movement of the board and the camera together, the same relationship used in a ‘gimballed set’. A gimbal set allows a fixed camera to move with a moving set, enabling, for instance, actors to appear to walk about defying gravity with ease, when the room/camera is itself the thing that is upside down. This technique has been employed in films including The Fly (1986) and as Rob Blazey pointed out when I was demonstrating and working on the mechanism, the film Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo (1984). The gimballed set up that Correspondence uses is closer to the strategy employed by Johnathan Glazer, director of the Jamiroquai music promo for the track ‘Virtual Insanity’ (1996). In this video, the floor and walls of a room are moving rather than the floor, making it appear that the central character and various pieces of furniture are moving in unnatural ways. Correspondence inverted the relationship of Glazer’s promo.

The effect of the gimballed broadcast of the piece began to create a different indexical relationship to the physical piece. If “cinema is the art of the index; it is an attempt to make art out of a footprint” (Manovich, 2001), then this live version becomes a Vertovian ‘direct cinema’. The monitor shows the ‘righted’ relationship, unscrambling the paradoxical signal of the ‘live film’ apparatus. I conceived of a possible installation staging that obscures the two apparatuses at work - the physical and the televised - so that an audience has to travel between them in order to afford a view of each that (might) confirm the other.

I was still not at a stage where I could start planning and building any sort of rig that would allow me to observe it hands-off. Instead, I constructed a pseudo-3d model with the animation package After Effects. I reasoned that I would need electromagnets, and used javascript to simulate magnets turning on and off. This was where I made my first serious error of judgment. Working as an animator, one becomes used to creating shortcuts that halve the time needed to create an animation. I programmed a board to move from 0 (centre) to -1 (left), right 1 to 0 (centre) and to +1 (right), turning off which piece moved and which piece did not. I then outputted this and reversed the final move, the +1right position to the centre which involved going left -1 back to 0. At this point, I thought I had come up with a way to use only 2 electromagnets to achieve the effect I was after, and save time in making mockups.

I ordered two electromagnets, chess pieces, rails to move the board and set about constructing the first iteration with a servo motor program via an Arduino micro controller.

Having finally begun to make a moving version (hand powered, but to my mind mechanically sound), I began to consider the temporal aspect of play. I devised a test circuit for servo motors moving into three positions linked to LED’s to signify each magnet but then wanted to work out an interesting interplay between the time taken between the moves of each player. My first inclination was to examine the possibility of using artificial intelligence (AI), researching Stockfish and other chess engines. Would these be modifiable so that a game could play from a specific position and then continue to play in stalemate? After experimenting with Stockfish and a suitable GNU, I found that although I could start a game form a specific position within Stockfish, I quickly ran into a baked-in rule within Stockfish, a threefold repetition rule that forced a draw. Enquiring with Tom Schofield, the task of recompiling open source software, after modifying the relevant code created a barrier to this route. A couple of promising leads seemed to go down dead ends. Tim Shaw and John Bowers offered a different route, building a simple AI using other open source tools. This is indeed an interesting route that at that time I had less of an inclination to go on with, but that I intend to research.

I attempted to find timings of Deep Blue versus Kasparov as one possible strategy to work out timings for the moves between pieces. Although there are PGN notation lists of all these historic games, I have so far been unable to find how long these games took. Another route for timings that I had explored in other work was examining the time it takes a signal to move a motor via a network signal. Tim Shaw demonstrated a ‘slow’ server as a way of seeding a random relationship between timings, which was also a route that I was encouraged to explore.

I began to research chess sites in a bid to find which chess engine each site used, and whether they allowed the repetition rules to be switched off. This search launched me into a third phase of the project. I found one such site, lichess.org, where the threefold repetition rule could be set to ‘claim’ mode rather than enforced. To discover this, I logged in as two human players and played a game to stalemate position and played a three move repetition for each piece. This interaction (switching between two humans) and the feeling that it gave of cheating (and logging in the system) made me reconsider the role of the moving chessboard/magnets / cctv piece and begin to think about the relationship between two ‘human versus human’ players playing online who were actually ‘driven’ by instructions from the simple program driving the motors. It struck me that in a sense, what I had stumbled upon was an inverse Mechanical Turk.

In the Mechanical Turk, a hidden human operator performs a pseudo automaton ‘as if’ it really were autonomous. In my new configuration, a machine, driving a program that moved physical pieces would pretend to be two humans playing chess online. This game, registering on the sites database could, or so I believed, last an infinite length of time, acting as a recording of each time the physical installation is played, recording its performance on the site’s database. In fact, I had not quite grasped a second chess rule - the 50 move rule - where the game again forces a draw until much further down the line.

A note on collaboration

I am indebted to Tom Schofield in guiding the stumbling grammar of the Arduino coding for Phase 2 of the project. He provided a framework for both receiving feedback through the serial monitor clearly, using arrays and an object oriented programming workflow to enable me to test and experiment more efficiently. During the third phase of the project, which I had hoped to develop once I began inspecting how Lichess operates using simple web developer tools, a series of conversations with Tom helped develop the piece.

I soon realised that the coding in Python for scripting the commands needed were well beyond my ability to implement. Whilst I was able to follow the logic of what needed to be done, and occasionally provided guesses as to things that would make the coding less sophisticated, the coding alongside several rounds of debugging were done by Tom. This process, together with discussions around approaches that provide neater, elegant solutions as against blunter strategies, was (for me at least) an insightful and enjoyable experience that enabled space to think about how these approaches altered the meaning and reading of the project.

This first version of Correspondence combines and plays off several elements - physical, broadcast, web based. It attempts an absurdist reductionism of commercial technology, a paradoxical encounter between a physical game and its televised transmission, and a reversal of the pseudo-automaton of Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk. The artwork ultimately lodges games played by a computer into a database as if they were human, hopefully going beyond the special effect of novel technologies in order to critique the way in which our engagement with technologies-as-human has become mundane and confused.

Thanks to Tom Schofield for python programming.